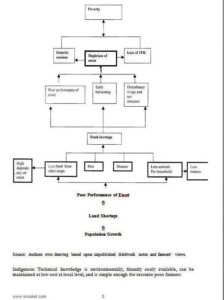

Figure l. Causes and Effects of Enset Crisis

Indigenous Technical knowledge is environmentally, friendly easily available, can be maintained at low cost at local level, and is simple enough for resource poor farmers.

Products, utilization and Classification

As has been mentioned earlier in the Southern part of Ethiopia enset growing farmers usually grow a mixture of various enset types. Farmers distinguish and classify enset plants based on their morphology and type of use, quality (taste, palatability colour etc.) and quantity of each distinctive product.

Fnset use and classification are very closely related. They not only identify a particular landrace and give it a unique place in their homestead but also tell us about its morphological and phenological characteristics, its maturity time, its use for food and various other purposes. Besides that they indicate its cookability, quality of its different products, taste, medicinal value and fiber quality (strength length and colour).

The cultivars have names and are distinguished by their appearance and use. The phenotype is distinguished by its height, the shape of the inflorescence, the colour of the leaf-sheaths and the mid-rib, appearance of strips or spots on the petiole, the width of the leaves, the length of the leafsheaths and the colour of the corm. (Zipel K. and Kefale A. 1995).

The uses are known by boiling the corm and testing its cookability, fermenting of leafsheaths and corm for human conception, by feeding animals as a fodder in the household, by using for construction, and by its medicinal values.

The corm, the pseudostem and the stalk of the inflorescence are the most important sources of human food (Kefale and Sandford, 1991).

Products of Enset

There are mainly four different products of Enset:

- Kocho (Wol. Uncha) is the decorticated (scraped-off) mass of the leafsheaths, which collectively make up the pseudostem of the enset plant.

- 2. Bulla (Wel. Itima) is the paste or powder formed after precipitation and dehydration, from the liquid, which was drained of from kocho and from the stalk of the inflorescence.

- Workay (Wel.Godeta) is part of the corm, which is pounded up by a harvesting/processing pestle with teeth.

- Amicho (Wel. Doysetida utta) is the boiled up corm, which has not been pounded but has been cut up into large chunks. Amicho is usually made from immature or matured female enset plants.

Uses of Enset

Food for Human: Kocho (Wol. Uncha), Bulla (Wel. Itima), Workay (Wel.Godeta) and Amicho (Wel. Doysetida utta) are eaten by humans.

Enset as an animal feed: all parts of enset are good sources for animal feed. Especially during the dry season the domestic livestock are fed on remnants of enset parts, which are not normally eaten by humans.

Fibre use: the fibre (Wel.golla) from enset is used in the weaving of products such as shopping bags, handbags, suitcases, sieves, pouches and mats. The variety, the age of the plant, and the way in which the fiber is extracted and stored all determine its length and quality (Kefale and Sandford, 1991). Farmers strongly believe that fibre extracted from the male is of a very high quality and strength.

Medicinal uses: some enset cultivars are believed to have medicinal value. Farmers use enset plants as medicines not only for human beings but also for their animals.

House construction and fencing: the moderately dried enset leafsheaths and midribs (which are locally called SUSA) are used for local house in enset growing areas. Farmers say susa is the most important raw material obtained from an enset and indispensable for fencing, wrapping and packing of every material and product and for tying and keeping animals in and around the house.

Enset is a decorative plant that gives grace to the homesteads and is used as a shade for humans and domestic animals. It is also a good windbreak to protect the small grass roofed farmers’ houses from strong wind, conserves soil and moisture.

Other uses: leafs can be used as an umbrella during rains, for serving oily food, for rapping butter, and spices, for sleeping and sitting. Stores water for Small domestic animals like chicken at the bottom part of the loose leaf sheathes.

Classifying Enset plants

Based upon the morphology and the type of use, farmers in North Omo tend to put enset plants into two categories, ” male–and “female”. Usually all the enset plants within a particular variety (as classified by farmers) are put into a single “sex” category, i.e. a variety is either male or female (Kefale and Sandford 1991). This division has nothing to do with reproduction but it is according to perceived characteristics of strength (male) and tenderness (female) (Kefale and Sandford). However some varieties seem to be neutral or can display mainly “male” characteristics and also display some “female” characteristics.

Because of their dual characteristics and purposes it is some times difficult even for the farmers to put them in one of these two categories. For example during a field survey farmers in Wolaita argued amongst themselves about one of the cultivars (Gefeteno) and finally agreed that there are some cultivars (in the third group) that shows some female and some male characteristics. However, one particular cultivar cannot fulfill both criteria at the same time.

Interestingly Wolaita farmers not only classify enset plants into male and female but also other crop species.

As a botanist divides plants and each subdivision is further divided, the male and female enset cultivars within each of the category have their own vernacular names. To date in north Omo alone about 156 enset cultivars are listed (Kefale and Sandford 1992/3). It is least probable that these are not distinctive cultivars, i.e. are not significantly different genetically, but merely represent a list of local names and many of the names represent cultivars, which are not distinctive (Kefale and Sandford 1991). People always refer to the vernacular name when planting, transplanting, managing, utilizing, giving and exchanging enset (Shigeta 1990)

Table- Differences Between Male and Female enset plants based on Farmers perceptions

| ‘Criteria | Male | Female |

| Maturity | Late maturing | Early maturing |

| Fibrosity | Strong, high in quality and quantity | Low strength, low in quality and in quantity |

| Size | Big | Smaller |

| Susceptibility to diseases and pests | Resistance | Susceptible |

| Corm | Fibrous (unpalatable) | Delicious, low fibre |

| Kocho | Ferments slowly | Ferments quickly |

| Leaves | Hard and stiff | Soft |

| Pseudostem and leafsheaths | Hard and stiff | Soft |

| Susa* | Hard and stiff | Soft and fragile |

| Average yield | High | Lower |

Source: Taken from Kefale Alemu and S. Sandford (1991), and further developed by the author

Indigenous knowledge and biodiversity/sustainability

Beyond its direct consumption value (source of food forage construction materials, row materials for local manufacturers. medicine potions, genetic resources etc.) enset has indirect values (leisure pursuit, ecosystem function, and ethical, moral and aesthetic values) values.

Among herbaceous plants enset has the biggest leaves (both in length and width). The nature of the leaf and its pseudostem helps it not only to cover the ground and protect the soil from direct rain damage, detachment and transportation of topsoil, but also it enables it to harvest water in its loose leaf sheath (pseudostem) pockets. Enset protects the soil from both wind and rain erosion throughout the year. The broad and long leaves of enset intercept the kinetic energy of raindrops and absorb it harmoniously into the pseudostem and the surface of the earth. Kena (1993) also indicated that enset fields when compared to other cop fields are less subject to erosion.

In addition it protects the soil from direct sun’s heat and decreases evapotranspiration both from the plants and from the land surface. It also has profound importance as a windbreak by decreasing the velocity of the wind (evapotranspiration will be considerably decreased). As a homestead plant it protects the farmers local houses from strong wind destruction. It is also the guardian of small coffee seedlings, vegetables, medicinal, and other useful plant species in homesteads. As its pseudo-stem is large and has a big corm and well-established strong roots it controls runoff and conserves soil and moisture.

But today land scarcity caused by population growth and the consequent food shortage has threatened this valuable plant. Shack (1963) has also mentioned that population density in enset growing areas of Ethiopia is exceptionally high. The average density in the enset growing areas as a whole is over 200 persons/ha, more than six times the national average (Pankrust 1993). As population growth is fast so the amount of cultivable land per capita will continue to fall. (Carrying capacity … the infinite human resources?)

According to the farmers there are some indications of the loss of the late maturing (male) enset plants because of the farmers immediate need to plant the female varieties, which are early, maturing and more palatable at their earlier stage. At maturity the total yield obtained from the male enset plant exceeds considerably the total yield obtain from the matured female enset plant.

Because of food shortage, farmers will be forced to consume the immature enset plants which has already seen as a threat to the sustained enset based farming systems. A threat to enset plants means a threat to the knowledge about enset that has been accumulated over time.

Loss of some plants and their habitat will ultimately cause loss of some of the above uses, services and cultural values. It seems that we are not only loosing the variety and the variability of living things and the complex ecosystems in which they occur but also the knowledge that has been gathered over time. One good example is obtained from Wolaita area. When farmers were asked how long enset products can be stored most of the middle-aged people said that they didn’t know. At present because of food shortage enset products will be consumed immediately after harvest i.e. they do not store enset products for many years as they did in the past. It is only when we talked to old people that they told us it can be stored up to eight years. From this we can learn that enset production was good in the past (because of low population density) and people could produce enough food and used to store it for some years.

The present generation does not store because of food shortage and as a result lost knowledge of storage techniques. Balick and Cox (1996) have also mentioned the many challenges facing ethno botanists in future years, particularly the rapid loss of biodiversity and the concomitant loss of indigenous knowledge systems.

Enset farmers repeatedly report that enset plants per capita are falling from year to year. The causes according to them are population growth and the subsequent land scarcity, which again leads the area’s people to food shortage. Fighting for their existence farmers always prioritize their immediate copping needs, which can change the whole farming/land use systems. They may tend to grow early maturing and short season crops. FARM Africa’s survey at Bolosso Sorie district of Wolaita has revealed the replacement of some of the homesteads by banana plants and the expansion of sweet potato farms from year to year. These are good examples. But why do farmers replace their fields by the above crops understanding the importance of enset and the bad consequence? The answer is that they are forced by food shortage to do and have no choice.

| Term | Origin/language | Meaning |

| Cultivars (Cultivated Varieties) | English | Plants that can be propagated not from seed but rather vegetative e.g. by stem and corm |

| Chegena | Ethiopia/Wolaita | The movement of the moon in a month |

| ITK | English acronym | Indigenous Technical Knowledge |

| Homestead | English | A farmhouse, with adjoining garden and crop |

| Wolaita | Ethiopia/Wolayta | A district in the Northern part of Ethiopia |

References

Alemu Kefale A. and Sandford S. (1991). Enset in North Omo Region. Farmers’ Research Project (FRP). FARM Africa. Addis Ababa. Ethiopia.

Balick M. and Cox P. 1996. Plant, people, and culture: the Science of Ethnobotany. Scientific American library. A division of HPHLP. New York

Bezuneh, T. (1993). An overview of enset research and further technological needs for enhancing its production and its utilisation. Proceedings from the International workshop on enset held in Addis Ababa. Ethiopia.

Kena. K. (1993). Soil problems associated with enset production. sustainable agriculture in Ethiopia. Proceedings from the international enset. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Kena. K. (1993). Soil problems associated with enset production. Enset based sustainable agriculture in Ethiopia. Proceedings from the international workshop on enset, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Rahmatho, D. (1993) Resilience and vulnerability: enset agriculture in Southern Ethiopia. Proceedings from the International workshop of enset, held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Shack WA (1966) The Guragie : A people of enset culture. Oxford University Press, London.

Shiueta M. (1990), False in-situ conservation of ensete ventricosum(Welw.) E.E. (Chesman) towards the interpretation of indigenous agricultural science of the Ari, Southern Ethiopia.

Zippel K. and Kefale A. (1995), Field guides to enset landraces of North Omo, Ethiopia. FRP Technical Pamphlet no.9, FARM Africa Addis Ababa